Classical fencing. Fencing as predominantly taught and practiced particularly in Europe and North America during the 19th century, which included separate systems of the foil, the epee (duelling sword), and the (duelling) sabre. Each weapon had a particular distinct school for its use. Instruction in each of the three weapons was available in accordance with the French method and in the Italian method. Other schools of fence available in classical Europe were the Spanish or Hungarian sabre. Classical fencing is taught and practiced without the use of electronic equipment of any kind and follows customs that were observed prior to the F.I.E. being established.

Modern fencing, a/k/a sport fencing. Fencing as predominantly practiced throughout in the world from the early 20th century and onward, particularly those that follow the rules of the F.I.E. (Federation Internationale d'Escrime, or International Federation of Fencing) or the similar rules systems, which include the use of electronic equipment for scoring, as well as relaxed conventions of priority (right-of-way).

Historical fencing, or historical swordsmanship. Fencing, or swordsmanship, as taught and practiced in Europe during the 14th through the 18th centuries. The "historical" period is said to be broken down into subperiods as follows:

Early historical. 14th and 15th centuries, the period that saw the publication of treatises on longsword combat by swordmasters and the beginnings of tactics and systems designed for civilian personal combat as distinct from military combat.

Middle historical. 16th century, the period that witnessed the sword being worn as a fashion accessory and the rise of both the Italian and the Spanish schools of the rapier for civilians.

Late historical. 17th and 18ty centuries. The 17th century was considered the golden age of rapier fencing, which was widely recognized as a scientific as well as artistic pursuit are clearly distinct from militaristic forms of swordsmanship. During this century, rapiers gradually shrank in size to increase their functionality, until it evolved into the so-called "smallsword". The 18th century saw the establishment of the dominance of the smallsword as the subject of fencing instruction and practice, as well as the rise of the French school who eventually would supersede the Italian school in being widely recognized as the leader of the European fencing discipline.

Parts of a Sword. For the various European swords, the parts are known as follows:

Pommel. The end of the handle used to secure the blade tang, usually wider than the handle and often in a rounded shape to resemble the fruit from which it earned its name, the "pomme," the French word for apple. It could be used as a bludgeon for thrusting.

Handle or Grip. The part between the pommel and the guard or hilt, designed to be held either by one or two hands. For certain swords such as the rapier, smallsword, sabre, schlager, or Scottish basket-hilted broadsword, this area was further protected by some form of hand or knuckle protection, such as a knuckle-bow extending from the crossbar, metal shell extending from the bellguard, or a basket comprising of part of the entire hilt guard.

Hilt or Guard. The part between the handle/grip and the blade, usually including a cross bar, to protect the hand from a weapon that might slide down the blade. Often the cross bar was accompanied by an additional guard in any of varying shapes such as a dish, bell/cup, clamshell, basket, swept-shaped bars, rings, or prongs for blade-catching.

Blade. The metal portion, usually having at least one sharpened edge and a sharp point at the extreme end, secured to the hilt by a metal tang that protrudes through the length of the hilt and grip to the pommel. The Italians and the French call the portion closest to the hilt the "forte" or strong part, and the portion closest to the point the "foible", or weak part. A groove often cut along the length of either or both flat sides are called "fullers", used for maintaining blade shape and firmness, and removing excess weight. They are also sometimes termed "blood grooves", pursuant to the common belief that the grooves aided in the removal of a sword blade from inside the target's body, by allowing blood to escape and air to enter the wound so as to alleviate the vaccuum effect of a human torso wound. However, this belief is deemed a misnomer by sword historians, who for medical reasons deny the significance of such a "vaccuum effect".

Early Historical Swords. The Early Historical period saw the use of broadswords, as continuing from previous centuries. Broadsword blades were straight and were used primarily for swinging, bludgeoning "cuts" and could also serve for thrusts with the point. This should not be confused with the Chinese dao, commonly known as a "broadsword", which is a misnomer and is actually a form of sabre or large fighting machete. These weapons were known for military use and for judicial combat, but since there was no known distinction between swords or swordsmanship for military combat versus for civilian, personal combat, these would also be known for self-defense or other personal combat, including early duels for personal matters of honor that were known to begin during this period. Such broadswords included the following:

Single-handed Broadsword. A broad sword with a simple cross hilt for the single hand. Sometimes called an "arming" sword, it was wielded as a back-up melee weapon by armored knights in the event during a joust after being unhorsed, or during military combat in the event of losing one's primary battle weapon such as an axe or mace. The cruciform shape of this sword may have contributed to its continued popularity among Christian knights during the Crusades, while the rest of the sword-wielding world, notably throughout Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia, abandoned straight swords and adopted curved sabres for military use.

Long Sword, also Bastard Sword or Hand-and-a-Half Sword. A broadsword longer in blade and handle than the single-handed broadsword, so that the sword could be wielded with either one or both hands.

Middle to Late Period Historical Swords and Fencing Weapons.The two fencing weapons of the middle and late historical periods are as follows:

Side-Sword, or Spada di Lato. A smaller version of the single-handed broadsword, often with an additional hand and knuckle guard, carried and used by civilians for personal combat. It is the precursor to the rapier. The early Italian treatises by swordmasters based their teachings on the use of the spada di lato, although the same teachings would become applied to the use of the rapier.

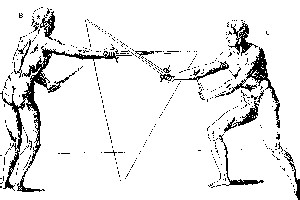

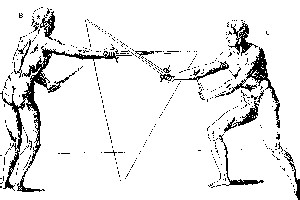

Rapier, also Espada Ropera, Spada di Filo, or Stricchia. A kind of sword usually worn and wielded in a civilian context in 15th to 17th century Europe, designed primarily for thrusting although capable of delivering non-fatal but potentially debilitating cuts with either edge. The blades and hilt designs vary in length and design, but generally the double-edged blades are long (blades ranging from 38 to 45 inches) straight and narrow. The hilts are equipped with some kind of hand guard such as a cup hilt, clamshell, or swept-hilt guard, and a crossbar or transverse bar that is usually held by the index finger, and sometimes the middle finger as well, for point control and leverage, as well as a knucklebow guard extending from the crossbar concavely down to the pommel. Frequently they were supplemented by a parrying dagger known as by the French as a main gauche (lit.: "left hand") wielded by the left hand for defense as well as for short-range attacks and blade-trapping tactics. Other supplemental weapons were taught and practiced as well, such as the cloak, the buckler, a second rapier (twin rapiers are termed "a case of rapiers"), makeshift supplemental weapons that happened to be available, or even the empty hand, preferably gloved in thick leather or mail. Unlike the classical schools of fence, rapiers were typically practiced and wielded "in the round", making use of lateral and circular footwork as well as linear footwork. Circular footwork was a particular trademark of the Spanish school of rapier. The "Preceding Point" rule of Classical fencing applies to rapier play only to a limited extent that it was important to extend the point or begin the cut prior to advancing or lunging. However, since the rapier was heavier and slower than the later classical weapons, the forward attacking step could be completed at about the same time as the thrust or cut without losing point control to properly aim the thrust. The rapier is the progenitor of the epee and the Italian foil, which unlike the French foil retains the rapier's cross-bar.

Smallsword. A kind of sword that evolved from the rapier, known to be used in late 17th century and more predominantly in the 18th century, shorter and quicker than the rapier (blades ranging from 34 to 37 inches). It is equipped with a small dish-sized guard, a cross-guard, and a knucklebow guard. Designed for thrusting attacks only, its edges were less sharp than the rapier, and were sharpened only to such extent as to discourage attempts to manually seize the blade. It was primarily taught and practiced in the French method, although the Italians used a similar weapon, a dimunitive version of the rapier, in a manner that echoed the Italian schools of rapier but making use of quicker movements allowed by the lighter and shorter weapon. The smallsword was also known to be supplemented by left-hand weapons, as was the rapier. The French smallsword and the Italian smallsword, or more accurately the "transitional rapier", would contribute to the development of the French and Italian schools of foil respectively.

Classical fencing weapons. The three classical fencing weapons, which are the same as the weapons practiced in modern fencing, are as follows:

Foil.

Epee (duelling sword).

Sabre (specifically, the duelling sabre).

Salle d'Armes, or Salle. A school of fencing, from the French, used in general in the international classical and modern fencing communities.

Maestro di Arma, or Maestro. A master of fencing, from the Italian. Some prefer the term Maitre d'Armes, from the French.

Provost d'Armes, or Provost. A teacher and scholar of fencing not yet a Maestro/Maitre but ranking above an Instructor.

Piste, or Fencing Strip. The long, rectangular area where actual formal bouts of fencing occur in the Salle.

Conventions of Priority, or Right-Of-Way In Classical fencing, fencing with either foil or sabre followed conventions that required a fencer to establish priority by preceding each touch with a valid threat, and to remove any valid threat upon oneself before attempting to touch the other. A valid threat is established upon full extension of the foil point, or sabre point or edge, toward the valid target area of the opponent. Once the threat is established, the threatening fencer has priority, or "right-of-way", to score a touch. The other fencer is then required to remove the threat, usually by parrying. If the threatened fencer disregards the threat and lunges, scoring a touch but also receiving a touch by the extended opponent's weapon, the point is against the fencer who disregarded the threat. However, in cases where there is only one touch, including cases where both fencers lunge and one happens to hit flat, or the point passes and slides off the target, but the other fencer's touch is sufficient, then no analysis of priority is necessary.

The Preceding Point rule of Classical Fencing. In Classical fencing in any of the three weapons, one rule is paramount: when attacking with the point, the point must be completely extended before the stepping forward in the lunge in order to aim and control the thrust properly. This rule also applies to lunging edge-attacks with the sabre: the weapon's edge must be extended and the cut must be executed prior to the completion of the lunge. When simultaneously executing a cut and retreating, the cut must be extended and executed before beginning the retreat step.

Classical fencing footwork. The various foot positions in classical fencing listed as follows (hand and weapon positions omitted):

Salute position.

En garde.

Lunge, or lunge-forward.

Reverse lunge, or lunge-back. From en garde, the weight shifts over the forward foot, which presses, shooting the rear foot backward and straightening the rear leg. Resulting position is same as lunge-forward.

Advance/Retreat.

Pass (Avant/Arriere).

Step Right/Left.

Advance/Retreat Right/Left

Gain. From en garde, the rear foot is placed forward where the heel is directly behind the forward heel, otherwise in a right angle similar to en garde. This step is used to adjust distance forward and usually precedes a surprise lunge.

Vault. From en garde with right foot forward, the forward knee straightens while the rear foot steps behind, to the right, and forward, thus pulling the forward foot to pivot around on the ball of the foot so that the back is turned forward. This step is used to evade a thrust by removing the torso from the line of attack.

Demi-vault. From en garde with right foot forward, the forward knee straightens while the rear foot steps behind, to the right, approximately to the right of the right foot. The right foot pivots around as in the vault, so that the right shoulder and a slight portiion of the back is turned forward. This step is a modified and more conservative version of the vault used for the same purpose as the vault.

Inquartata. From en garde with right foot forward, the rear foot steps behind and to the right, approximately to the right of the right foot, and the rear leg straightens while the forward knee remains bent. This step is used for the same evasive purpose as the vault or the demi-vault.

Intagliata. From en garde with right foot forward, the forward foot lunges diagonally forward to the left. Otherwise same as a lunge. Used to attack at an angle, or as an evading attack by a right-handed fencer to evade a thrust by a left-handed adversary.

Side-lunge. From en garde with right foot forward, the rear foot lunges to the left and the forward leg straightens to the left. Same as a lunge but to the left, and with the feet reversed.

R'assemblement. From en garde, the forward foot is pulled in directly in front of the rear heel and both knees straighten. The torso inclines slightly forward. This step is usually performed with a stop thrust in response to an attack to the low-line, i.e., the abdomen or flank.

Italian stop-thrust position. From en garde, the forward foot is pulled behind and past the rear foot, and both knees straighten, with the torso inclining slightly more forward than in the r'assemblement position.

Rohdes stop-thrust position. Same as r'assemblement but with the feet perched on the tips of the toes.

Passata Sotto. From en garde, the rear foot and leg extends backward while the forward knee bends acutely, while the torso fully inclines forward parallel to the floor. Used to duck an attack, in conjunction with a timed thrust.

Balestra. From en garde, the rear foot presses down and shoots the forward foot forward in a lateral leap. The rear foot follows, airborn, until both feet land simultaneously forward in a "gain" position. Usually this move is followed immediately by a lunge, although it may be followed by a reverse lunge or some other step to deceive the adversary who prematurely anticipates and relies on the expected lunge forward. This move is an aggressive and athletic move that covers great distances in short time but momentarily sacrifices control.

Redoublement. From the lunge, the rear leg bends and the rear foot is advanced shoulder-width's distance behind the forward foot, momentarily re-establishing en garde, followed immediately by another lunge from en garde. Alternatively, the rear foot may be advanced up to a "gain" position prior to the second lunge, to cover further distance.

Creep forward or backward.

Reprise. From the lunge, a recovery back to en garde, followed immediately by a repeated lunge forward.

Lines of Attack. Any of the four general target areas of the body. In classical fencing terminology, the torso is divided into four areas where an adversary fencer may attack, for the defending fencer to protect. The target area on the body is divided down a central vertical line from the chin to the groin (the "center line" also used in other martial arts systems especially Wing Chun kung fu and Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do) into the "outside", the target area closest to the front foot, and the "inside", the target area closest to the rear foot. The target area is further divided along an equator between the chest and the abdomen, the upper part being the "high" and the lower part being the "low". Hence, any attack is said to target either the "high" or "low" lines of attack, and the "outside" or "inside" lines. Hence, there are four possible "lines of attack", being high-outside, high-inside, low-outside, and low-inside.

Parry. A deflection of an attack. In fencing, particularly in foil and epee fencing, there are eight classical parries, with one auxillary parry, as follows:

Sabre Parry. In sabre fencing, the classical Italian seven parries, with one auxillary parry, are as follows:

Classical Fencing Blade Work. The terms for blade movements in classical fencing are as follows:

Extend. From any parry position, to aim the point at the nearest target area on the opponent and to either attack or threaten the corresponding target area, i.e., from a parry in sixte, extension should point to the opponent's line of quarte. An extended point toward an unprotected valid target area is a valid threat to that area, in which case an extension would also be deemed a "threat". Usually followed by a lunge or an advance, or any combination of the two.

Engage. To make blade contact with the opponent's blade without striking or pushing, such that they merely touch and adhere. An engagement should close the opponent's nearest line of attack, i.e. prevent the opponent's blade from pointing directly at a target area or from being able to do so without merely extending.

Change of engagement. From engagement, to gently move the opponent's blade laterally from one line to another, thus opening a line of attack on the opponent. Also, from engagement where one's blade is closed out of line by the opponent's blade, to circularly disengage and re-engage to close the same line from which one's blade begain its movement.

Disengage. To remove one's blade from engagement with the opponent's blade. Usually accompanied by an extension to a new line of attack, or even the same line of attack after managing to circle around the opponent's blade.

Circular re-engage, or counter re-engage. To change engagement by disengaging and re-engaging a blade to the same position from which the blade originated its movement.

Lateral re-engage. To engage a blade that has disengaged laterally to a new line of attack from which it had previously been engaged, in order to re-close and reclaim the opening of that line.

Derobement (day-robe-MONT). From an extension, to evade an opponent's attempt to make blade contact by quickly removing one's blade from its position. Usually followed by immediately returning it to its original position, or switching to a new line.

Trompement (tromp-MONT). From a guard position (point slightly elevated), to evade an opponent's attempt to make blade contact by quickly removing one's blade from its position. Usually followed by immediately returning it to its original position or by moving to a different line.

Coupe (Koo-PAY) An alternate means of changing engagement in the same line, usually when engaged in the high line, by quickly sliding one's blade up away from the opponent and along or near the opponent's blade over its point, and then descending one's point on the other side of the opponent's blade to threaten a new line, or the same line from which the preceding engagement took place, and simultaneously opposing the opponent's blade out of line. This involves the unusal and risky act of bringing one's point up and momentarily away from any target area.

Lateral parry. To parry a thrust by moving the blade laterally from one line to another. A parry is performed without a push or a strike but with the same pressure as an engagement.

Counterparry, or circular parry. Like a circular or counter re-engage except to parry a thrust rather than merely engaging the blade, the blade parries the opponent's thrust to the same line from which it began its movement.

Riposte (rePOST or rePAHST). Upon having executed a parry, to attack immediately thereafter by extending, usually in the same line of attack from the parry position.

Remise (reMEEZ). Upon one's attack having been parried, to immediately disengage and then immediately renew the attack to the same or a different line. Sometimes coupled with a redoublement or creep (see footwork).

Appuntata (Ah-poon-TAH-tah). Upon one's attack being parried and as the riposte begins, to yield back with the riposte and to parry same while remaining in blade engagement, and simultaneously to close that line and open a new line of attack, followed then by a renewed attack while opposing the opponent's blade out of line.

Feint To threaten a line on the opponent for the purpose of provoking a reaction from the opponent. Usually followed by a thrust to a different line.

Prise de Fer (PREEZ de FARE), or Bind. Any attempt to seize and bind the adversary's blade with one's own. Methods of pris de fer include the lie, croise, envelopment, and flacconade.

Liement (lee-ay-MONT). To seize and lock the opponent's extended blade, usually when it is extended in the high line, by engaging the opponent's foible with one's forte near the guard and then dropping the point, followed by a lateral change of engagement to open a low-line attack while the opponent's foible is trapped. Usually followed by an attack to the opened line.

Croise (Kwah-ZAY). To edge-out an opponent's extended blade, usually when it is extended in the high line, by engaging the opponent's foible with one's forte near the guard and then dropping the point and the guard slightly, forcing the opponent's point off-line. This movement opens a low line and is usually followed by an attack to that line.

Envelopment. (Ahn-vehl-op-MONT). To stall an opponent's extended blade, usually when it is extended in the high line, by engaging the foible with the forte and dropping the point, then returning it in a circular pattern to its original position. Although seemingly nothing has changed, it buys time for an attack and interrupts the opponent's momentum.

Flacconade (Flah-kon-AHD). To avert an opponent's extended blade, usually when presented to the center line and near the equator, by engaging in second and closing it out, simultaneously opening the line of attack to the low inside. Often combined with a reverse lunge.

Yielding parry. To parry and yield with the forward movement of a thrust by retracting at the same time to maintain contact, for the purpose of redirecting the thrust. Usually followed by circularly changing direction once the attacking thrust has past in order to riposte. This kind of parry is used to counter and reverse a pris de fer attack, allowing the adversary to change the line of attack before applying the parry.

Intercepting parry. To counter an attempted pris de fer attack by way of a counterparry or counterbeat after allowing the adversary to change the line of attack, as the following lunge develops.

Cavez. To counter an attempted pris de fer attack by using leverage against an opponent's blade by engaging its foible with one's forte and opposing, precluding the adversary from changing the line of attack.

Beat. To strike the opponent's blade aside, usually in order to open a line of attack. A strong, unexpected beat may succeed in disarming the opponent.

Froissement (Fwoss-MONT), or Explusion. To violently turn aside the opponent's blade by using a quick push or twist of one's blade, thus simultaneously opening a line of attack.

Glissade (Gliss-AHD), or Coule (Coo-LAY), or Glide. From engagement, to glide or slide down the length of the opponent's blade, extending to threaten a line of attack, usually to provoke a reaction.

Parry volante (voh-LONT), or flying parry. To parry by quickly sliding back along the length of the opponent's blade, toward its point, which involves the unusual and risky act of bringing one's point away from the opponent's target areas. Usually followed by a dramatic circular moulinet (windmill) using the momentum from the parrying movement, in order to return one's point toward the opponent and to extend the point into a new line of attack.

Pressure. To gently press with blade against the opponent's blade, usually for the purpose of eliciting a reaction or to open a line of attack.

Thrust in Opposition. Also known by some as a "tension", to attack with a thrust, usually with a lunge, while simultaneously opposing the opponent's blade to close its line of attack.

Un-Deux, or One-Two To begin an attack by fully extending into any line, which if parried or closed out by the opponent, is followed by a second attack to a different line. Unlike a feint-thrust combination, the one-two involves a initial real attack with a contingent second real attack.

Double (Doo-BLAY) To begin an attack by fully extending into any line, which if parried or closed out by the opponent, is followed by a disengagement, circular re-engagement, and second attack to the same line, usually while opposing the opponent's blade.

Stop thrust To extend the point and touch without advancing or lunging, relying on the opponent's forward movement. In foil or sabre, making the touch prior to being hit by the opponent's attack is mandatory for the touch to be valid. Usually performed using the r'assemblement (See footwork above). In sabre, a stop-cut is like a stop-thrust except using a cut with the sabre edge.

Time thrust A variant of the stop-thrust, making a touch while evading an opponent's attack. Usually performed by way of inquartata, vault, demi-vault, or passata sotto. (see footwork above.)

Push-cut. The primary cutting attack of the sabre in the Italian school, which cuts by way of hitting with the edge and extending forward with the blade.

Draw-cut. The secondary cutting attack of the Italian sabre, ordinarily reserved for cuts across the front of the torso and, in some cases where permitted or in self-defense situations without applicable rules, across the front thigh. It is performed by hitting with the edge and simultaneously slicing the edge back, as commonly done in Asian sword arts with swords such as the katana, and the Chinese dao.

Moulinet, or molinello. (lit., windmill). To describe a wide circle with the point. The trademark of Italian sabre bladework, it is used to generate momentum, speed, and force for proper parries and cuts. Italian moulinet cuts are generated by a pivot of the elbow of the sabre arm. In contrast, the Hungarian school of sabre, followed by most modern sabrists, is known for its moulinets generated from the wrist.

Technically not a weapon but a practice tool based on the 18th century French smallsword, known by the French as a "fleuret", the foil is the smallest and most flexible of the three classical weapons, and with the smallest hand guard, which was often limited to the size of a small dish. Designed for safety as are all "foiled" weapons by definition, the foil has a flat nail-head in lieu of the swordpoint, covered by a button. In an age where duels to the death were engaged over matters of honor and etiquette, the practice of fencing with foils included "rules of convention", or priority, for the purpose of teaching proper defense for application in real duels with sharp weapons, and to avoid double-suicide during such duels. The rules, also known as "right-of-way", required a fencer, when threatened with the point of an adversary's foil, to remove, or evade, or otherwise neutralize the threat before initiating an attack. For scoring purposes, in the event of both fencers touch each other in a "double-hit" that would otherwise represent two injured duellists, the point would be awarded against the fencer who attacked without priority. Double-hits where neither fencer had priority would be considered a nullity. The valid target area is the torso, including the neck under the collar and above the groin. Valid touches are made with the foil point only, and with at least one-inch bend to the blade to represent sufficient penetration.

A weapon frequently used in civilian duelling in the 19th century, the epee is longer and stiffer in blade than the foil, with a larger bell guard to conceal the entire hand. During the classical period, the training version of the epee was fitted with a "point d'arret" over the point, which is a three-pronged cover that served to not only blunt the point but also to catch onto the target of the opposing fencer to confirm the touch. In modern practice a blunt covering replaced the point d'arret. The practice of epee fencing did not involve rules of convention, and thus the first to make a touch has priority, as an analogy of the rule of "first blood" sometimes adopted for duelling purposes. "Double-hits" would be awarded against both fencers. Valid target area is the entire body. Valid touches are made with the epee point only and with sufficient blade bend.

A weapon frequently used in civilian duelling in the 19th century, the sabre is the only classical fencing weapon whose edge may be used to score a valid touch. The sabre has a "true" edge, representing the sharpened edge facing the direction the knuckle-guard bows out, and a "false" edge, with three inches from the point representing the sharpened edge on the opposite side, the remaining length of the edge being dull. The version of the sabre for training, the point is curled in toward the guard, forming a rounded point for safety. The sabre, like the foil, is practiced with conventions of priority. The valid target area is everything from the waist up, except in some cases the upper front leg was also an allowable target.

Pictured above: hilt close-up of the three weapons of classical fencing, to wit: the foil, epee, and sabre (bottom to top).

Standing erect, feet at right angle, forward foot toward adversary.

Feet shoulder-width apart and at right angles, forward foot toward adversary, 60% weight over the rear foot, knees bent.

From en garde, rear foot presses down and rear leg straightens to shoot forward knee forward. Forward knee rests directly over the forward instep.

Advance: from en garde, the forward knee partially straightens and extends forward and the forward foot half-steps forward, temporarily forming a double-shoulder-width en garde position (similar to the Shaolin "L" stance or half-horse stance), then immediately followed by the rear foot to resume en garde.

Retreat: from en garde, the rear knee partially straightens backwards, and the rear foot half-steps backward, temporarily forming a double-shoulder-width en garde position, then immediately followed by the forward foot to resume en garde.

Pass Avant: from en garde, the rear foot passes in front of the forward foot toward the adversary and settles a shoulder-width's distance forward from the forward foot, toes pointing perpendicularly to the direction of movement and with the passed forward heel raised. Momentarily, the weight is mostly over the passing foot, which was originally the rear foot. The forward foot, which is now behind the passing foot, immediately follows by passing behind the passing foot toward the adversary and settling into en garde.

Pass Arriere: from en garde, the forward foot passes behind the rear foot away from the adversary and settles the ball of the foot a shoulder-width's distance behind the rear foot, toes pointing toward to the direction of movement and with its heel raised. Momentarily, the weight is mostly over the passed foot, which was originally the rear foot. The rear foot, which is now in front of the passing foot, immediately follows by passing in front of the passing foot away from the adversary and settling into en garde.

Step Right: From en garde with right foot forward, the right foot steps to the right, followed by the left foot to resume en garde.

Step Left: From en garde with right foot forward, the left foot steps to the left, followed by the right foot to resume en garde.

Advance Right: From en garde with right foot forward, the right foot steps diagonally forward and to the right, followed by the left foot to resume en garde.

Advance Left: From en garde with right foot forward, teh left foot steps diagonally forward and to the left, followed by the right foot to resume en garde.

Retreat Right: From en garde with right foot forward, the right foot steps diagonally backward and to the right, followed by the left foot to resume en garde.

Retreat Left: From en garde with right foot forward, the left foot steps diagonally backward and to the left, followed by the right foot to resume en garde.

Creep forward: From a lunge, the rear leg bends to place the rear foot slightly forward. Then, the forward foot immediately launches forward the same distance that the rear foot had advanced, for a redoublement. Used to advance short distances upon having already completed a lunging attack, often in conjunction with a renewed attack such as a remise or appuntata.

Creep backward: From a lunge, the rear leg bends and the torso shifts slightly backwards to enable the forward foot to be placed slightly backward as well. Then, the rear foot immediately shoots back the same distance that the forward foot retreated into another lunge. Used to retreat short distances upon having already completed a lunging attack, especially when the initial lunging attack passed the adversary and more distance backward is needed to allow another attack to be renewed.

Prime (PREEM). Protects the low-inside line with the elbow and pommel up.

Second (seKOND). Protects the low-outside line with the hand pronated.

Tierce (TEERCE). Protects the high-outside line with the hand pronoted.

Quarte (KART). Protects the high-inside line with the "false" edge, hand slightly pronated. When using the Italian foil, the hand is supinated and the "true" edge is utilized.

Quinte (KEENT). Protects the high-inside line , particularly the low area of this line, using the "false" edge, with the hand pronotated and the point slightly lowered and pointed out to the side.

Sixte (SEECKS). Protects the high-outside line with the "false" edge, and with the hand supinated.

Septime (sepTEEM). Protects the low-inside line with the hand supinated.

Octave (ock-TAHV). Protects the low-outside line with the "false" edge, and with the hand supinated.

High Septime. An auxillary parry that protects the high line at or close to the center line, by parrying upwards using the "false" edge, with the blade horizontal and the hand supinated.

Prime. Same as foil and epee.

Second. Same as foil and epee.

Tierce. Same as foil and epee.

Quarte. Same as foil and epee except the hand is supinated and parry is with the "true" edge, as with all sabre parries.

Quinte. Protects the high line upwards, with the hand pronated (knuckle guard up) and to the outside, blade horizontal with slight incline upward.

Sixte. Protects the high line upwards, knuckle guard up but hand to the inside, blade horizontal with slight incline upward.

Septime. Protects the high line outside beside the face, hand is at the high outside and the blade points down along the outside line past the bicep or shoulder.

Demi-Circle. Same as foil and epee "Septime" parry.